30th December 1943

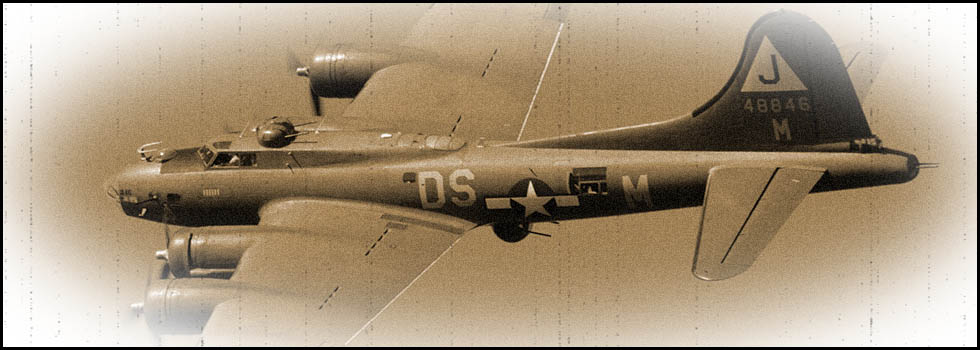

Boeing B-17F # 42-30674 "Destiny’s Tot"

8th Air Force

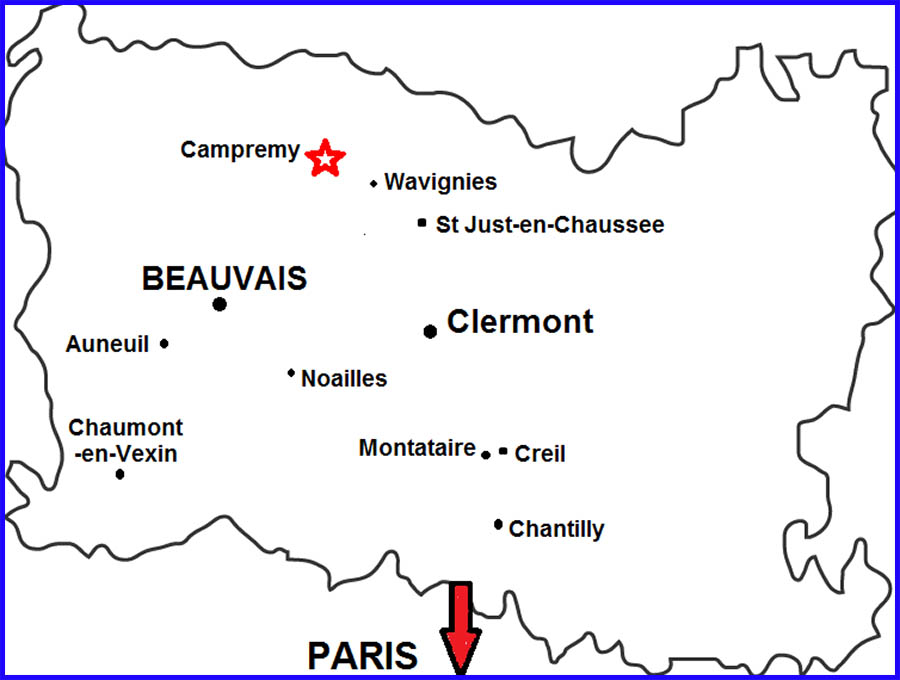

Campremy (Oise)

Copyright © 2016 - Association des Sauveteurs d'Aviateurs Alliés - All rights reserved -

On 30th December 1943, during a mission targeting the IG Farben chemical industries in Ludwigshafen, Rhineland, the 8th Air Force lost two escort fighters P-47s "Thunderbolts", two B-24 "Liberators" and three B-17 "Flying Fortresses" which crashed in various places in the Oise departement.

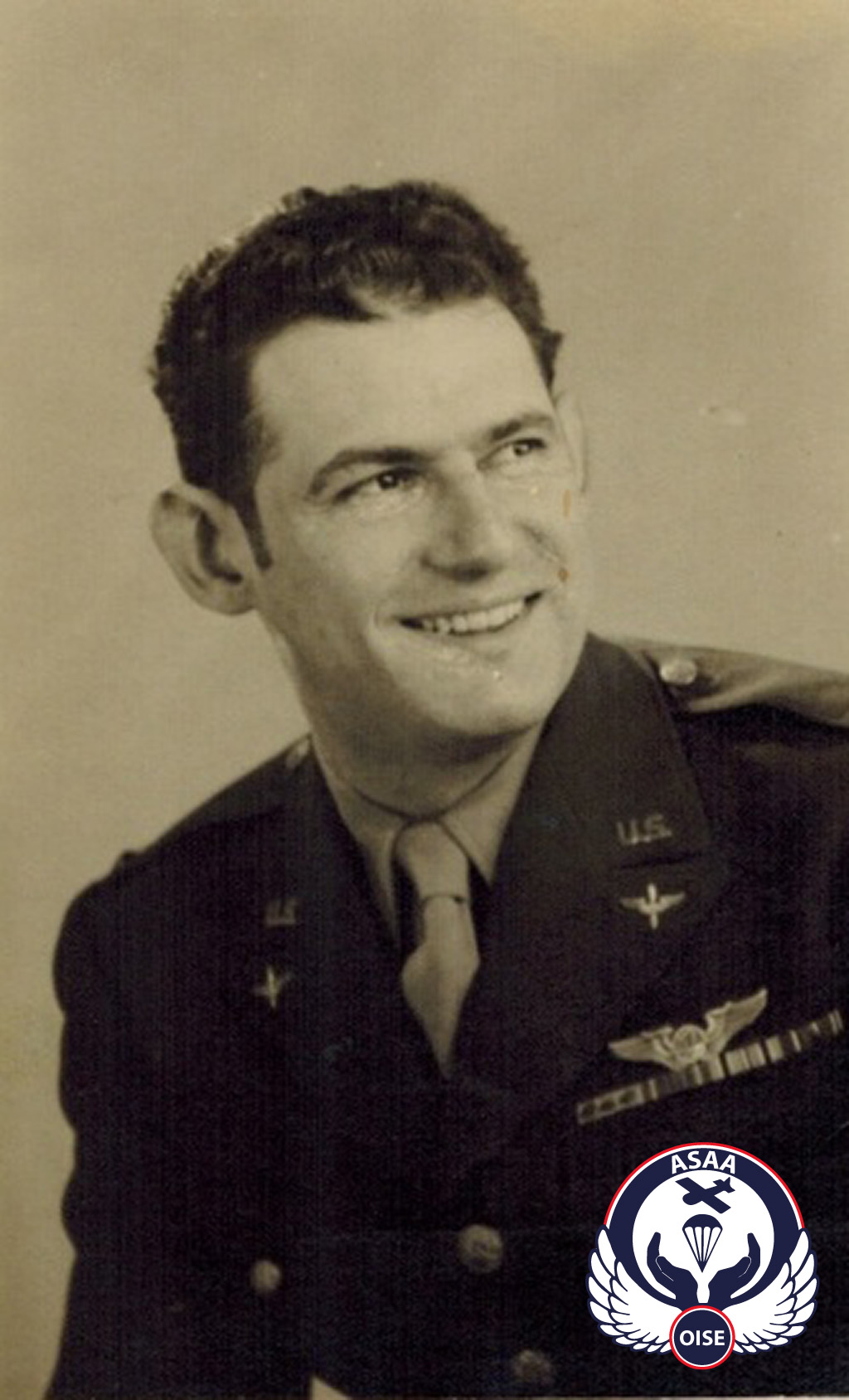

Among these aircraft, the B-17 # 42-30674 "Destiny's Tot" of the 95th Bomb Group, 336th Bomb Squadron, had been designated to take part in this perilous raid. It was piloted by 1st Lt. Richard M. Smith who was carrying out his 13th mission that day.

95th Bomb Group

The crew of "Destiny's Tot" :

| 1st Lt. Richard M. SMITH | Pilot | 22 | Evaded | Breckenridge, Minnesota |

| 2nd Lt. William H. BOOHER | Co-pilot | 23 | Evaded | Chicago, Illinois |

| 2nd Lt. Louis FEINGOLD | Navigator | 24 | Evaded | Brooklyn, New York |

| 2nd Lt. Warren C. TARKINGTON | Bombardier | 23 | Evaded | Kearney, Nebraska |

| T/Sgt. Kenneth A. MORRISON | Top turret gunner | 24 | Evaded | Phoenix, Arizona |

| T/Sgt. Alphonse M. MELE | Radio-operator | 36 | Evaded | Bronx, New York |

| S/Sgt. Jerry ESHUIS | Ball turret gunner | 21 | Evaded | Zillah, Washington |

| S/Sgt. Robert F. ADAMS | Right waist gunner | POW | LaGrange, Ohio | |

| S/Sgt. Anthony ONESI | Left waist gunner | 22 | POW | Niagara Falls, New York |

| S/Sgt. Thomas G. O'HEARN | Tail gunner | 27 | POW | New Hampshire |

Front row, left to right :

Warren C. Tarkington (bombardier), Murray Ball (navigator replaced by Louis Feingold),

Richard M. Smith (pilot) and William H. Booher (co-pilot)

Back row, left to right :

Robert F. Adams (gunner), Tony Onesi (gunner), Alphonse M. Mele (radio-operator),

Thomas G. O'Hearn (tail gunner), Robert Southard (ball turret gunner replaced by Jerry Eshuis)

and Kenneth A. Morrison (top turret gunner, engineer)

Early in the morning, the B-17s of the 95th Bomb Group took off from the English airbase of Horham, Suffolk. After being integrated in the vast armada, the bombers set course for France. After crossing the English Channel, the French coast was crossed between Etretat and Dieppe. Then the four engined aircraft set course for Germany. They were soon joined by American and British fighters escorting them on part of the way before turning back because of their insufficient range.

B-17s in formation (Wikipedia)

The waves of bombers, evolving into tight formations at 30,000 ft, continued their flight to the Reich. About 1:00 pm, arriving over the target, the bomb bays were opened. Maintaining their course while following the flight leader amid bursting shells of Flak, the bombs were dropped on the target and its surroundings.

The "Destiny's Tot" was hit as it began the return trip. A burst struck the navigator’s compartment, another severely damaged one of the four engines, causing a major oil leak.

Now flying on three engines, the aircraft lost altitude and was gradually distanced from the rest of the formation. The crew now knew they will have to cross, alone and unescorted, first northern France and then England.

Lurking behind the stricken four-engined aircraft, a Messerschmitt-109 and then six Focke-Wulf 190 seized the opportunity to attack the isolated prey. On board the B-17 the gunners returned fire from their machine guns, trying to shoot down the attackers. At the rear of the aircraft, S/Sgts. O'Hearn, Adams and Onesi were injured. In the ball turret, Jerry Eshuis was also wounded. The repeated enemy attacks quickly made the bomber difficult to control. The aircraft was full of holes, hydraulic and electrical systems were inoperative and the radio compartment was on fire.

The "Destiny's Tot" was flying over France. The order to abandon the aircraft was given by 1st Lt. Smith. The intercom was destroyed, everyone spread the word and realised the position he was in. Parachutes were fixed. The crew members helped each other in turn to evacuate the lost bomber. 1st Lt. Smith, having tried to keep the aircraft in the line of flight, was the last to leave the plane which was now at only about 13,000 ft.

Completely abandoned, the "Destiny's Tot" continued its flight for a few minutes before plunging to the ground. It crashed and exploded in the early afternoon in a field near the village of Campremy (Oise).

Crash site near the village of Campremy

Several people observed the airmen falling from the sky hanging from their parachutes. They immediately tried to rescue these men before the arrival of the Germans. The fates of the ten members of the crew of "Destiny's Tot" were going to be very varied.

S/Sgt. Thomas G. O'Hearn landed north of Fumechon. Although seriously wounded, he managed to undo his parachute. Unable to move, he laid on the ground. French people rushed to him. They realised his condition required urgent attention. It was impossible to move him. Having no idea what to do about the situation, they had no choice but to advise the Germans, in order to save his life. Thomas O'Hearn was therefore captured and evacuated to hospital.

S/Sgt. Robert F. Adams landed in a field near the village of Catillon. French people get rid of his parachute and find that he was seriously injured. They managed to carry him and hide him in a barn. Warned quickly, a French doctor administrated first aid to the airman. Noting the severity of injuries, it was decided to hand him over to the Germans.

S/Sgt. Anthony Onesi also came down near Catillon, a short way away from S/Sgt. Robert F. Adams. He too was injured. Two French people rushed towards him. Seeing the state of his injuries, the two men had no choice but to warn the Germans.

In the afternoon, a vehicle arrived at the scene. The German ambulance took Onesi in charge, then headed to the barn where Adams was semi-conscious. The two airmen were taken to the Compassion hospital in Domfront (Oise) which was under the control of the German Army.

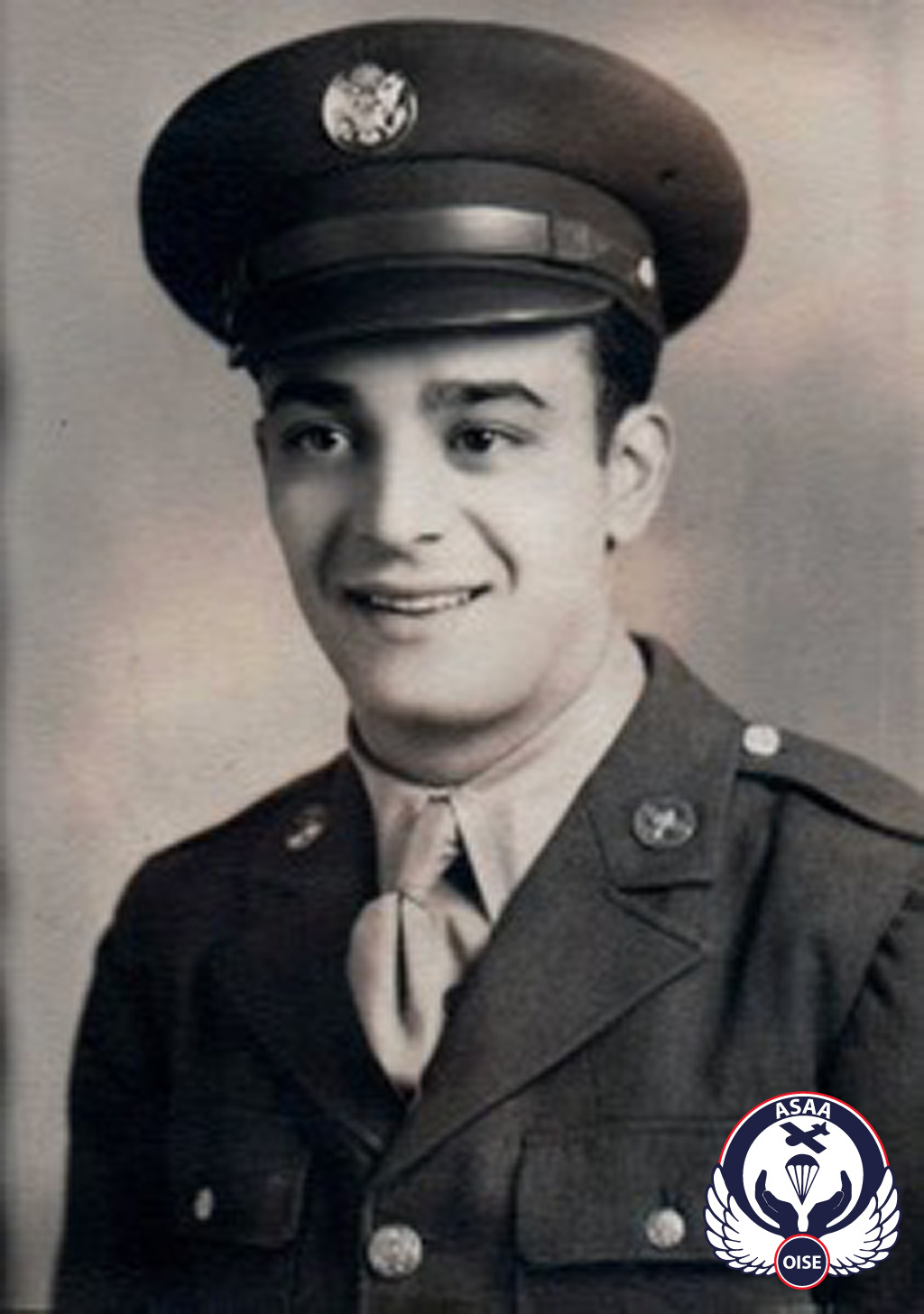

S/Sgt. Anthony ONESI

After several weeks of care and closely guarded, O'Hearn, Onesi and Adams, were sent to prison camps in Germany until the end of the war.

The other seven crew members were to be luckier.

After landing and have quickly got rid of his parachute, T/Sgt. Kenneth A. Morrison saw six French people rushing to meet him. Using his translation book, Morrison asked where the Germans were. He decided to go in the opposite direction. After some time, he hid in a thicket and then later in a haystack. Soon, a farmer appeared and advised him to return to hide in the bushes and wait. After nightfall, the same farmer came back to Morrison. He gave him civilian clothes then told him to go along the railway tracks where he will be able to take a train. Walking in the dark along the tracks, Morrison met another Frenchman who accompanied him until they reached a station. There, Morrison met a man of Polish origin, Adolphe Kozuira, who then took him to Arthur Jullien, his brother-in-law, in Saint-Just-en-Chaussée. Kenneth A. Morrison was hosted by this family until the morning of 1st January 1944...

T/Sgt. Kenneth A. MORRISON

S/Sgt. Jerry Eshuis, the ball turret gunner, landed near the village of Catillon. Immediately, a group of people approached him and helped him take off his equipment. During the exchange of fire with the German fighters, Jerry Eshuis was hit above the right eye and received shrapnel in the shoulder. His most serious injury, however, was at the top of his right leg. He was quickly taken to the village of Catillon where he saw his friend "Bob" Adams without being able to talk to him. The Gorge family took Eshuis in charge. The reception in this farm was very warm. He was summarily treated and provided with civilian clothes. His airman’s equipment was quickly stuffed into a bag and hidden. The women there prepared a meal and then Eshuis went to a bedroom in the house to sleep for two hours.

S/Sgt. Jerry ESHUIS

During this time, the Germans were plying the sector, particularly through the village in search of the downed airmen. Jerry Eshuis was awakened and hidden under hay in a barn. Fortunately, the Germans were just passing through and did not search the farm. The alert passed, the airman returned to the small room. He was to remain hidden by the family Gorge until 1st January...

The navigator 2nd Lt. Louis Feingold and the bombardier 2nd Lt. Warren C. Tarkington landed very close to one another in the countryside north of the town of Saint-Just-en-Chaussee. Tarkington slightly injured his ankle during landing. The two airmen, surprised and happy to meet each other, went to meet a Frenchman who made signs to them from a hay wagon pulled by horses. Soon, a second wagon arrived. Both airmen asked the farmers to be separated because this gathering may well attract the Germans. One of the men, of Belgian origin and speaking some English, took Feingold and Tarkington on his cart towards a wooded ravine and then asked them to get off and await his return. Now alone, the two aviators got rid of their flight equipment.

2nd Lt. Louis Feingold 2nd Lt. Warren C. Tarkington

As agreed, the man came back later with civilian clothes and proposed that he accommodate them although he had no contact with the Resistance.

Now dressed like real peasants, Feingold and Tarkington, accompanied by the Frenchman, made their way to a main road. On the way, they met another man on a bicycle who spoke perfect English. Sent by Jean Crouet, this man, named Viaud, told the two airmen that they should follow the road to a crossroads where there were a number of telephone wires. This was where they would be met later.

At around 7 pm, as it was getting dark, Jean Crouet, a member of the local Resistance who lived in Saint-Just-en-Chaussée, arrived. He whistled and found the two airmen at the agreed location. After crossing a ploughed field and an orchard, he took them first to an old house, where they stayed for an hour, and then to his home. His wife Madeleine prepared dinner. With the Germans still looking for the airmen, Jean Crouet was forced to hide them in his cellar. A doctor came to treat Tarkington's ankle.

Early the next morning, Jean Crouet, who worked as an engineer-chemist, took the two Americans into the Weeks factory where he was also the Director. Feingold and Tarkington were hidden in a tunnel under the plant, only going back to the office of Jean Crouet at mealtimes when the workers were absent.

Feingold and Tarkington remained in the plant until the evening of 1st January.

The radio-operator T/Sgt. Alphonse M. Mele landed in a field west of the village of Wavignies. He declared himself to be an American to the five people, including two women, who had rushed towards him. One of the Frenchmen, Gilbert Santune, quickly took Mele to the barn of a nearby farm. The airman was left alone. His rescuer came back around 6:00 pm with civilian clothes. Mele’s airman equipment was hidden in a bag and the two men headed on foot to the home of Gilbert Santune. Immediately, his wife prepared food.

Late at night, Mele was moved to a farm where he found the co-pilot William H. Booher and the pilot Richard M. Smith.

Wavignies

On the outskirts of Wavignies, 2nd Lt. William H. Booher was collected immediately on landing by a whole group of people. Very quickly, he was taken to a house where he was given civilian clothes. Later that evening, he was taken into a barn and then inside a farmhouse where he had the joy of seeing Smith, his pilot, and the radio-operator Mele.

2nd Lt. William H. BOOHER T/Sgt. Alphonse M. MELE

1st Lt. Richard M. Smith was the last to leave the aircraft. While floating in the air hanging from his parachute, a Messerschmitt-109 approached and began to circle around him. This was a very worrying situation for Smith, who thought that the German pilot was about to shoot him. Instead, he clearly saw the airman waving to him, a gesture to which Smith replied with great relief, before seeing the enemy aircraft go away. Smith also ended up landing near the village of Wavignies. A man ploughing his field indicated to him the direction to take to escape the Germans. He went to hide in a hedge and decided to wait for dark. After nightfall, three armed civilians appeared. One carried a bag of clothes. They indicated to the pilot that he must get changed and then all headed to a house in the village of Wavignies. Smith was put in front of a fourth Frenchman who questioned him and then he was transported in the boot of a small car to a farm where he met Booher and Mele again.

1st Lt. Richard M. SMITH

That evening, Georges Jauneau, "Captain Jacques," leader of the Resistance group of St Just-en-Chaussee, met the airmen briefly. He was a severe and strict man concerning security. He explained that they were now in the hands of the French Resistance but that they just have to be patient.

In the evening of the next day, the 31st December, "Captain Jacques” came back to meet the three Americans who got into a small lorry to go to Saint-Just-en-Chaussee. They were taken into a vacant two-story house owned by Mr Dubois, located at the bottom of the rue de Paris. Smith, Booher and Mele were to stay there for a few days. The three men wondered what will happen in the days to come. They knew that the local Resistance was now organizing the next stage of their escape. Meanwhile, they had to wait patiently and the days were long. They spent a lot of time playing cards. The monotony was broken by visits from Paulette, the wife of "Captain Jacques", who was responsible for bringing them meals several times a day.

Kenneth A Morrison

In the morning of the 1st of January 1944, having come from Chantilly, Jean Lacour took Kenneth A Morrison in charge at the house of the Julien family at Saint-Just-en-Chaussee. The two men took the train to Chantilly. After a short stop at Jean Lacour’s house, the airman was taken right next door to the house of Yvonne Fournier who had the haberdashery shop “La Belle Jardiniere”. Morrison was lodged until the 3rd January at the back of the shop. After a visit of a gendarme, Louis Despretz and Edmond Bourge arrived. These latter were very involved with the Resistance. Edmond Bourge took Morrison on the back of his motorcycle to the Cafe de la Paix in the neighbouring town of Gouvieux. The owner, who soon turned up on his bicycle, was no other than his mate Louis Despretz. After the meal Morrison was taken nearby to the home of Innocente and Betty Lauro. Here was being lodged since a very short time, an American airman of the 379th Bomb Group, S/Sgt. Milton J. Mills Jr. who has been wounded in the leg. The B-17 in which he was radio-operator was similarly shot down on the 30th December during the same mission on Ludwigshafen. The two airmen were able to swap stories of their adventures. A few hours later and again on the motorcycle, Edmond Bourge took Morrison to the rue de Conde at Montataire. The airman was welcomed by Marie Dorez and her husband, the parents-in-law of Edmond, who run a wholesale business in cheeses.

At this time, Morrison did not know that he will be lodged with the Dorez for a whole month. This long stay was going to create a certain complicity between the airman and the family, particularly with Jacqueline, aged 18, the youngest member of the family. Pulling legs and joking often gave rise to really good laughs. In spite of the continuous presence of German troops in the town, Jacqueline sometimes took the airman to a games room on the other side of the road where they could play table tennis. The owner of the place was heartbroken to learn that "a so young and good looking young man" was “dumb”.

On the 27th January, S/Sgt. Milton J. Mills was taken by Edmond Bourge on his motorcycle to the Dorez’ house. The two airmen were delighted to see each other. Two days later, Mills left to stay with Jules and Hortense Duchateau who lived at the other end of the street. The fact that the two houses were near each other allowed the airmen to meet almost on a daily basis.

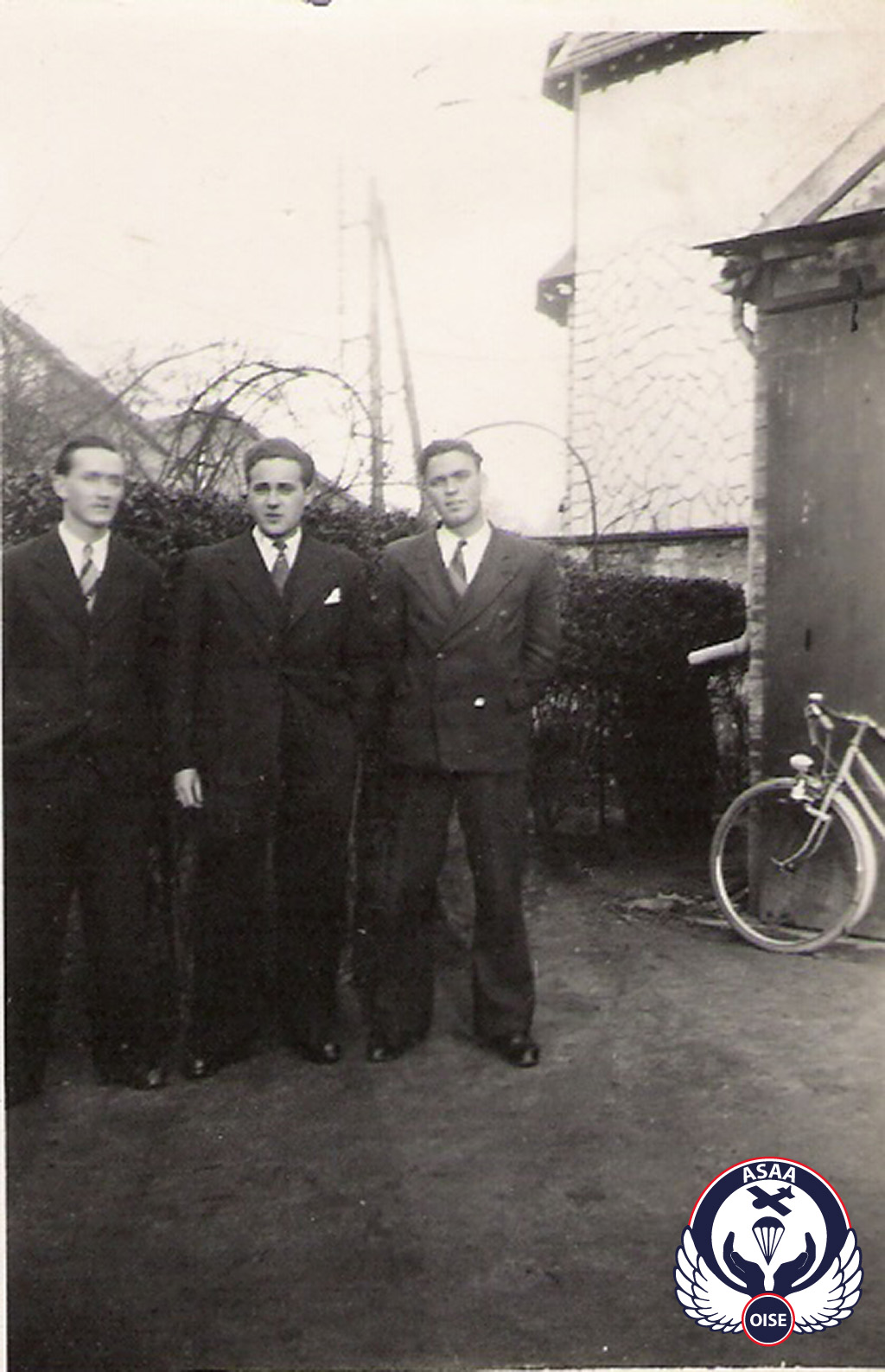

Milton J. Mills Jr., Edmond Bourge

and Kenneth A. Morrison.

Photo taken in January 1944 at the Dorez’ house

in Montataire.

Having obtained false identity papers through Edmond Bourge, Morrison and Mills left Montataire on the 4th February in Mme Dorez’ car. They were taken to the station at Creil where they met “Rolland” (Leslie Atkinson). He gave them train tickets and went with them as far as Amiens.

Once in Amiens, Morrison and Mills were taken by “Rolland” to a lady who was going to lodge them. On the 12th February, he came back to pick up the two Americans and took them to a house in the town which proved to be too small for the two airmen. Finally they were going to be lodged by Georges Tourdes and his family. They were going to stay here until the 14th March, the date at which Joseph “Joe” Balfe came to collect them. Once again, Mills and Morrison were moved to be lodged in another part of the town, by Rene Lemattre, a hairdresser living near the Saint-Roch station. About fifteen days later, Benjamin Lefebvre arrived by car and drove the two Americans to Hornoy-le-Bourg, about thirty kilometres to the West of Amiens. In the village, they should have met with other English and American escapers to continue their journey by taking the train, but in the meantime the railway track had been sabotaged and destroyed.

Morrison and Mills were taken to the house of the Paire family who lived in the village. They stayed there for one night. The next day they were moved to Jean Fourrage’s house and waited for several hours. Rene Lemattre then came to get them and took them to Amiens. They were going to stay with him until the 5th April.

On the 5th April, “Joe” Balfe and Benjamin Lefebvre turned up with a group of airmen. They were given tickets for the train to Paris. They were told that they were to be divided into small groups and how they should behave. They must follow “Joe” at a distance. Morrison and Mills learned that Jean Fourrage* and his mother had been arrested by the Gestapo on the 2nd April at Hornoy.

*Jean Fourrage was shot on the following 8th May in the Gentelles wood, near Amiens. His mother was deported to Germany.

The train arrived in the middle of the afternoon in Paris. At the Gare du Nord, two men and a woman made themselves known to “Joe”. One of the new guides took over and went down into the underground with a group including Morrison, Mills and two other American airmen.

He took them to the 5th arrondissement, to Mrs Olga Christol, rue Edouard Quenu, where they were going to stay until the 11th April. The airmen were subsequently taken over by the “Burgundy” escape network.

In the evening of the 11th April Genevieve Soulie came to collect the airmen and guided them to the Gare d’Austerlitz. She told them to follow a young woman carrying a suitcase (Genevieve Crosson alias “Jacqueline”) and then they took their places in the night train which was to take them towards the Spanish border..

Arriving in Montauban without incident the next morning, they had to wait in a town park before getting a train in the direction of Toulouse. During the three hours wait the airmen anxiously but finally without mishap, got through the controls. They mingled with the crowd and then took a train to Pau, at the foot of the Pyrenees, where they arrived in the evening of the 12th April.

Once past the controls and out of the station, their guide went with them into the town. They were then told to follow a young girl in a white dress on a bicycle (Joan Moy-Thomas). This lady, of English origin, led Morrison’s group through the streets of Pau to the home of Countess Anne de Liedekerke who put them up for the night.

On the 13th April Rosemary Maeght, who was from Massachusetts and Joan Moy-Thomas visited the airmen. They announced that their departure was due for the next day. But something happened which obliged Morrison and his group to wait.

They finally left Pau on the 15th April and were taken into the region of Oloron-Sainte-Marie. The airmen reached a barn where they lay down in the straw and rested. During the night of 17th to 18th April, having been joined by another group, two passeurs guided the escapers in their climb to the Spanish border. They walked until the next morning, arriving at another hut.

The frontier near the Pic d’Anie was crossed during the night of the 19th to 20th April. The guides accompanied them as far as a shelter on the Spanish flank. Before leaving them the guides told them to follow a stream in the direction of Isaba. After a short rest the airmen continued their scramble down the mountain. On crossing a bridge in the middle of the morning they were apprehended by the Spanish Guardia Civile. The airmen were interrogated and then took to Isaba where they were detained in a barn.

On the 21st April, well guarded, they were taken in a bus as far as Pamplona which they reached in the evening. They were interned for three weeks. During this time, the Consulate tried to get them liberated as soon as possible.

On the 14th May, they were transferred to Alhama where they stayed until the 28th May, at which date they reached Madrid and then Gibraltar. In the night of the 29th to 30th May an aircraft at last took them back to England.

Jerry Eshuis

On the 1st January, Jerry Eshuis was transferred by Dr Caillard from Catillon to the Chateau de la Borde, in Sains-Morainvillers. The imposing residence was the property of Count Jacques de Baynast whose wife, Colette, was no other than the sister of General Leclerc de Hauteclocque who was fighting in Africa.

Without anaesthetic, having drunk a glass of alcohol, Jerry Eshuis prepared to be operated on by Dr Georges Debray, aided by Dr Edmond Caillard, in one of the first floor rooms. Having put a rag in his mouth, his hosts retrained the airman tightly by the arms and legs, while the two doctors extracted the fragment of shell lodged in his groin. The cleaned wound was then stitched up.

Jerry Eshuis stayed in the Chateau for the time of his convalescence which was going to last several days. He had to be able to move around without too much difficulty before being able to continue his escape.

Château de La Borde

Richard M. Smith, William H. Booher, Alphonse M. Mele……..and Jerry Eshuis

At Saint Just-en-Chaussee, after a week spent in the town, the comings and goings around the usually empty house where Smith, Booher and Mele were lodging seemed to awaken suspicions in the neighbourhood. One evening Georges Jauneau moved, in great security, the three Americans to another house. They were welcomed by Paul Begue and Yvonne Fossier who had just become parents to a little Paulette.

Very generously the new hosts decided to let the airmen had their only bedroom while they slept elsewhere. Smith, Booher and Mele took it in turns to use the bed.

During the day, they had to be discrete. They were confined to the house but in the day the presence of the family helped to pass the time. A few rabbits from the hutch ended up as stew in cooking pot, allowing the rations imposed by the enemy to go further.

On the 9th January “Capitaine Jacques” came to inform the three Americans about their next move.

On the morning of 10th January “Capitaine Jacques”, accompanied by Paul Begue, Smith, Booher and Mele went on foot to a factory in town where they were surprised to meet their machine gunner Jerry Eshuis who had arrived that very morning from the Chateau de la Borde.

The airmen had not been provided with false identity papers. As a consequence, before getting into the vehicle, “Capitaine Jacques”, gave each one a 9 mm calibre pistol which they must use if the Germans tried to arrest them.

In spite of the risks, the long journey to Paris went without incident. Once in the capital, the driver made a telephone call. At the door of an apartment block he dropped off the four airmen, who each gave him back their arm before he made the return journey.

Smith, Booher, Mele and Eshuis were taken in charge by Mme Rose Coulon, aged about sixty, who had an apartment in the Boulevard Pereire, in the 17th arrondissement.

Here they met Pierre de Jandin and his sisters (related to Rose Coulon).

However, at the end of two days the lacks of space inside the apartment mean that two of them had to be moved. Jerry Eshuis, who was still suffering from his wound and William H. Booher stayed.

In the evening of the 11th January, Richard M. Smith and Alphonse M. Mele were taken on foot by Pierre de Jandin and another man who spoke English. After almost an hour walking in the streets of Paris they arrived in the rue des Capucines, in the 9th arrondissement. The two airmen were entrusted to Albert and Madeleine Poncelet, concierge of the building housing the offices of the Canadian Pacific Railways. The guide, who spoke English, turned out to be related to the Director of the Railway Company. On the 5th floor of the building, Smith and Mele had to keep a low profile because German officers occupied the 3rd floor. However Albert Poncelet had no hesitation in occasionally taking his guests to the cinema or the theatre even if the two airmen did not always understand the language.

For their part, in Rose Coulon’s flat, Eshuis and Booher just waited. They needed false papers to be able to continue their escape. They were taken into a “photomaton” near the Champs Elysees. The Americans took advantage to “visit” the occupied capital, passing the Arc de Triomphe and the Eiffel Tower and also going to the cinema amusing themselves at the propagandist German news.

At the Poncelet’s Smith and Mele were interrogated. During their stay they had their photographs taken to make false papers.

On the 19th January “Claudette” (Marie-Rose Zerling) came to the Poncelet’s, explaining to Smith that she was going to take him with her. Needing a radio operator, “Claudette” tried to convince Mele to stay in France and to work with her in the Resistance. Although flattered by this proposition. Mele refused, his priority was to return to his family in New York.

Before leaving, the airmen met an officer who was at the head of the organisation (Lucien Dumais). He announced that they were going to return to England by boat and that that they will be in London within a fortnight.

Like many other escapers, they were going to benefit from the “Shelburn “escape line, created at the end of 1943 by Leon Dumais and his radio operator Raymond Labrosse, two Canadian agents of the Intelligence Service of MI9. With the help of contacts in Paris and in Plouha, in Brittany, it was going to prove to be a much faster way of repatriating airmen. During night operations, corvettes of the 15th Flotilla of the Royal Navy allowed them to regain England, having crossed the Channel, in just a few hours.

On that 19th January, “Claudette” took Richard Smith by underground train. On the way they “picked up” another American airman, 2nd Lt. Morton B. Shapiro, before getting to the Gare Montparnasse. The airmen were handed over to two guides and took their seats in a compartment on board a night train leaving for Brittany. For this long journey, they were advised especially not to talk, but to pretend to sleep or read a newspaper...

On 20th January, arriving in Saint-Brieuc, gendarmes controlled papers in the station under the watchful eye of the German Police. From now on the airmen were inside the forbidden coastal zone. They now had to take the little local train, often crowded, to Plouha. Other guides took turns, including Adolphe Le Trocquer. At the Plouha-Ville stop, a young girl of 18, Marie-Therese Le Calvez, took Richard Smith and Morton Shapiro in charge as well as two other American airmen who got off the train, S/Sgt James King and S/Sgt Walter Sentkoski. She took the four of them to her house, a two storey building in the village, where she lived with her mother Leonie.

On the 20th January", in Paris, it was Mele’s turn to be taken to the Gare Montparnasse where he joined Booher, Eshuis and other evaders. Like Smith they travelled as far as Saint-Brieuc. The various checkpoints crossed, they took the departmental train which took them to Plouha. The airmen were then guided to the hamlet of Ville-De, a hamlet of Plouha, and to the farm of the Monjaret family.

Throughout the days which followed, a total of 16 Allied airmen were on standby, spread out amongst local families around the village of Plouha. Now everything depended on the weather conditions. At this end of January strong opposing winds and the bad state of the sea obliged the Admiralty to postpone the evacuation.

Finally, after long days of uncertainty, on the evening of the 28th January the coded message “Bonjour tout le monde à la maison d’Alphonse” was sent out and confirmed on the BBC amongst a whole litany of other messages all in mysterious terms. It triggered off the operation “Bonaparte” by the Royal Navy which was to take place that night. It was the long awaited signal. During this moonless night, the evaders were taken in small groups as far as the “Maison d’Alphonse”, whilst avoiding the German patrols. This empty house, property of the Gicquel family, was 1,500 m from the Cochat cove, the intended place of departure.

It was about 11.30 p.m.. Gathered together, all received the last strict recommendations from “Leon” (Lucien Dumais). This last stage of the way leading them to freedom necessitated the most absolute silence on their part. They were asked to empty their pockets, and to get rid of any paper or object which would allow them to be identified if things turned out badly. The briefing finished and then surrounded by their guides, the evaders went into the blackness in single file on the little path. Through the moor and thickets they came through the gully to the beach, some of the guides leading the way.

The beach of the Cochat cove which later became Bonaparte beach.

It was about midnight. Regrouped in the shelter of the rocks and hidden from the German gun position at the Pointe de la Tour, the evaders from then on just had to wait patiently for the arrival of the gunboat.

It was about midnight. Regrouped in the shelter of the rocks and hidden from the German gun position at the Pointe de la Tour, the evaders from then on just had to wait patiently for the arrival of the gunboat.

Posted half way down the cliff, one of the guides, Job Mainguy, flashed at regular intervals the agreed signal of the Morse code letter “B” (for Bonaparte), by means of a torch.

At about 1:30 am the surboats appeared in the penumbra and landed on the beach. After the exchange of passwords and the unloading of suitcases containing arms, the airmen embarked on board the surboats to rejoin the gunboat anchored off the Taureau beacon.

One month after their aircraft had been shot down, Smith, Booher, Mele and Eshuis landed in the port of Dartmouth, England.

During this Operation Bonaparte I, a total of 16 airmen refund freedom: 13 Americans and 3 British.

Also evacuated on that night were Vladimir Bouryschkine “Val Williams” (who had run the “Oaktree” Organisation), a Russian named Ivan (both escaped from Rennes prison) and a French resistant.

Louis Feingold et Warren C. Tarkington

On the 1st January, they left the Weeks factory and were taken a few steps away from there to the house of Leon and Idamir Hary, a family of bakers who were going to lodge them until the 3rd January.

On the evening of the 3rd January they returned to Jean Crouet for the night.

In the evening of the 4th January there was another change. They were welcomed by Georges and Helene Rousseau where they stayed for two days.

On the 6th January, towards the end of the afternoon, Jean Crouet came to collect them. The two airmen followed him at a distance on foot in the streets up to the edge of town. A lorry overtook them and then stopped. Feingold and Tarkington hid in the back. They learned that Smitth, Booher, Mele and a fourth airman of the crew (Eshuis) were safe, but that three had been taken prisoner and another had been killed (!!)

At the exit of Saint-Just-en-Chaussee the lorry stopped next to two cars parked on the side of the road. The two airmen got into the second car while the other car showed the way. About fifteen kilometres further on they arrived in Clermont. Gaston Legrand who lived with Odette Sauvage and her son Edmond, aged 17, were going to look after the two Americans in the house which they rent in the rue du Chatellier, on the upper part of town and right next to the Kommandantur. Animated by a strong patriotic sense, this family from Clermont had already lodged other American airmen who had been shot down in the region in September 1943.

On arriving at the house of Odette and Gaston, Feingold and Tarkington were surprised to meet a young bombardier of 19 years of age, 2nd Lt. Edward J. Donaldson, who had been lodged since 31st December. His aircraft, of the 379th Bomb Group, had been shot down on the 30th December during the same raid on Ludwigshafen.

Edmond and Odette Sauvage, Gaston Legrand

Elsewhere, Odette ran a small milk parlour in the town centre and lived with Gaston in the flat over her premises. Gaston, who had been taken prisoner at the German invasion in 1940, had managed to escape in March 1941 from the camp at Royallieu and was demobilised. There only remained Edmond to keep the airmen company throughout the long days in the little house in the rue du Chatellier, being joined each evening by his mother and Gaston.

During their stay in Clermont, the airmen were often visited by Simonne Bernadet, a dressmaker aged 35 who spoke English. She came to support the airmen and supplied them with books to help them pass the time.

The Leclercq family, from the neighbouring village of Breuil-le-Sec and friend of the Legrand-Sauvage also came to meet the airmen. Lucien and Maurice Leclercq and their mother Suzanne often supplied the Americans with food, clothes, shoes and cigarettes.

Two days later, on the 8th January, three other American airmen arrived at the house of Odette Sauvage and Gaston Legrand : 2nd Lts. Glenn E. Camp Jr., Jarvis H. Cooper and Sgt. Neelan B. Parker. Donaldson thus met his pilot, his navigator and one of his machine gunners again.

Very quickly a great camaraderie was established between the six young Americans who were considered as members of the family. The audacious Odette managed to regularly outwit the Germans by diverting food with the complicity of her son Edmond. Gaston, a butcher by trade, managed to find meat by going out at night to kill animals.

The situation was not without risk. An escape plan through a rear window and across the garden was devised by Edmond, in case the German came to the house. Right next to the Kommandantur, the escapers could often discretely watch, through a window in the front, the comings and goings of German soldiers on foot or on motorcycle.

On the 20th January, Simonne Bernadet announced to the airmen that four of them were going to leave in the afternoon of the next day. Donaldson, Feingold and Tarkington who had spent the most time here were chosen to go. By drawing lots with a pack of cards, Parker was the lucky one to be the fourth one chosen. Camp and Cooper had then to wait an extra week before leaving Clermont. No-one knew it that day but the drawing of this single card sealed the fate of the 2nd Lts. Camp and Cooper. In May, they were to be taken prisoner in a train not far from the Spanish border and sent in captivity to Stalag Luft I, in Germany, until the end of the war.

It is finally on the 21st January in the morning that the four men took leave of their two companions, with a mixture of joy and sadness. Two guides took them to the station on foot whilst Lucien Leclercq checked the route and kept watch from a car.

On arriving in Creil the airmen were separated. Feingold and Donaldson were lodged by Marcel Gerardot and his wife, rue Henri Pauquet, while Tarkington and Parker went to the house of Paul Toussaint, rue Somasco, along the River Oise.

On the 22nd January, Marcel Gerardot took Feingold and Donaldson back to the station at Creil where they found Tarkington and Parker who had been brought by Mme Toussaint. Two guides, including Edmond Sauvage, took over the four airmen and escorted them by train as far as Noailles. Then they were handed over to a man who took them by car to Robert Eckert’s farm.

Robert Eckert’s farm at Noailles

About twenty airmen were lodged there in 1943 and 1944.

This farm, surrounded by high stone walls, was a safe place lived in by a most patriotic family which had, in the recent past, already lodged other Allied airmen. To limit the risks, the two little girls of the family, aged 10 and 7, did not go to school so as to avoid eventual “gossip”. Feingold, Tarkington, Donaldson and Parker were lodged until the 24th January at the Eckert’s house. During this stay, Tarkington suffered from abdominal pains but there was no doctor to see him.

In the evening of the 24th January, while the airmen were about to have their evening meal, Gilbert Thibault, a bailiff and founder of the escape line “Alsace”, arrived in Noailles in a lorry, accompanied by a coal merchant. The order was given to get their belongings and board the lorry. A hot cooked goose which was ready to eat, was wrapped in paper. Marthe Eckert entrusted it to Louis Feingold who clutched it to his body to keep him warm during the journey. The four airmen were taken to Auneuil, to Gilbert Thibault’s home.

In the evening a doctor came to see Tarkington. Whereas Feingold and Tarkington were lodged by Gilbert Thibault, a neighbouring blacksmith took charge of Donaldson and Parker.

Gilbert Thibault took it upon himself to obtain false identity cards. Donaldson, whose photos were not regulation, was even taken to a photographer in Beauvais, known to Thibault.

Gilbert Thibault took it upon himself to obtain false identity cards. Donaldson, whose photos were not regulation, was even taken to a photographer in Beauvais, known to Thibault.

On the 26th January, an American airman, T/Sgt. Ray P. Reeves, was taken off by the coal merchant. During their stay, the hairdresser, Hilaire Lemaire came to cut the hair of all the escapers.

In the morning of the 27th January, Gilbert Thibault and Hilaire Lemaire took the five airmen to the station at Chaumont-en-Vexin where they took the train leaving for Paris. Arriving at the Gare Saint Lazare, they went down into the underground and were taken to Marguerite Schmitz, rue Rochechouart, in the 9th arrondissement.

This lady, age 55, already lodged two other airmen. One of them, F/Sgt. Richard W. Aitkin-Quack, was a fighter pilot in the Royal Air Force, the other, “Olaf” Hanson, called “Fred”, apparently Norwegian, reckoned on coming from the crew of a Flying Fortress. Very soon, contradictory affirmations of this latter claim seemed to be very suspicious. The airmen became conscious, according to certain things, that he was probably an imposter. They warned Gilbert Thibault and Marguerite Schmitz. After the meal “Claudette” (Marie-Rose Zerling) arrived in the apartment and moved Parker and Donaldson to the home of Countess Bertranne d’Hespel, rue Maspero, in the 16th arrondissement.

Coming back a little later in the evening, “Claudette” took Feingold and Tarkington away. Coming out of the underground station Pasteur, she accompanied them to the house of Mme Kocera-Massenet, rue Ernest Renan, in the 15th arrondissement, where they were to stay a few weeks. “Claudette” announced to them that she had previously organised the escape of their companions Smith and Booher and promised to come and visit them in the following days. At the house of their hosts, Feingold and Tarkington made the acquaintance of Jean Kocera, the son of the owner, and of his friend Raymond Mauret who also belonged to the Organisation.

As arranged, “Claudette” who spoke English perfectly, came to visit them on a regular basis, bringing razors, cigarettes, etc... They met her for the last time on 3rd February. Long days followed. The two airmen waited patiently for the date of their next transfer.

On 11th February, Feingold and Tarkington had a visit from Marcel Cola. He introduced himself as their new contact and he interrogated them. He announced the arrests of “Claudette” and of Mme Schmitz by the Gestapo*.

* In the night of the 4th to 5th February 1944, about ten soldiers and civilians appeared at Marguerite Schmitz’ flat, armed with pistols and machine guns. German Police! Immediately her apartment was searched. The English airman, Richard W. Aitken-Quack and “Olaf” were captured. They were all then taken by car to 101, rue Henri-Martin, in the offices of the band of Christian Masuy, who was in the pay of the Germans. Grilled with questions to try to discover the ramifications of the network, Mme Schmitz was tortured, water boarded, only giving a few unimportant details. Condemned to death at the end of April 1944, she escaped deportation and was incarcerated in Fresnes prison until the Liberation.

“Claudette” (Marie-Rose Zerling) was arrested in the afternoon of the 5th February as she was visiting Mme Schmitz. The apartment had been transformed into a trap. Carrying a large sum of money and compromising documents, “Claudette” was likewise interrogated on many occasions, tortured and imprisoned. Condemned to death she was deported in August 1944 to the Ravensbruck Concentration Camp. Her parents were also arrested and deported. Only her father would fail to return.

On Monday 21st February, Marcel Cola came once again to meet the two airmen to take their photos. He advised them that they probably were going to leave Paris that week and continue their escape along the coast.

The 23rd February Jean Kocera and Raymond Mauret visited Feingold and Tarkington, warning them that they were going to leave the next day. Indeed, in the evening of the 24th February Jean Kocera took the two airmen on foot to the Gare Montparnasse. There they found Raymond Mauret who had brought two other airmen : Sgts. Olynik and Quinn. They all settled into a reserved compartment on board a night train going to Brittany.

A short time before, the little departmental train leaving from Saint Brieuc had been cancelled by the Germans. On the 25th February, at about nine o’clock, the airmen and their guides alighted at the station in Guingamp. Jean Kocera gave them each a folded newspaper to make them easily recognised by the new guides amongst the passengers. The group soon had a young girl and a man alongside while Raymond Mauret and Jean Kocera left. Olynik and Quinn followed the young girl while Feingold and Tarkington were taken by the man who left them in a house opposite the station. An hour later the young girl and the guide came back and led the two airmen to rue du Grand Trotrieux, to the house of Louise Chareton, where they met up with Olynik and Quinn.

During the course of the afternoon, "Leon" Dumais came to meet them and they were interrogated.

At about 8.00 p.m. a young guide arrived and took them discretely in the darkness to the garage of Francois Kerambrun in rue du Vally. The four airmen hid under the tarpaulin in the back of a little gas powered lorry. They were soon joined by others and then the vehicle left Guingamp. At several stops in the surrounding countryside he picked up other escapers who were packed in the back. That evening 17 airmen were thus taken to the coast. Arriving on the outskirts of Plouha, was the first contact with the local Resistance group. Nine of the escapers got out, and then a little further on the other eight, including Feingold and Tarkington. These latter spent the rest of the night hidden in a barn of a farm in Ville-De (at Françoise Monjaret's) where everything had been prepared to welcome them.

The day of 26th February was spent just waiting. In the evening the message “Bonjour tout le monde à la maison d’Alphonse” was sent out by the BBC and was heard in spite of all the background noise. The second embarkation operation was on tonight. At 9.45 p.m. two men came to collect the eight airmen and took them in the darkness to the “Maison d’Alphonse”, the final stage of their journey before returning to England. They found the other nine escapers there. “Leon” (Lucien Dumais), the Canadian chief of the Shelburn mission was there. He gave them all the instructions as to how to get to the beach and told them that the boat will arrive between 2 and 3 o’clock in the morning. Just as at the preceding operation “Leon” asked them to get rid of their money and their false papers.

At about 11.45 p.m. in single file and in the most total darkness, the airmen followed their guides, holding hands across the fields and the little lanes leading to the sea. That night, due to the increase in German patrols, the airmen and their guides did not pass through the gully but hurtled down the steep cliff, one after the other, towards the beach. They grouped together in the shelter of the rocks and rested whilst awaiting the arrival of the gunboat. The tide was high that night. Around 1:45 a.m., four rowboats landed on the beach.

Bonaparte Beach

Bonaparte Beach

During this black and cold night of February it is just the wait for the rowboats.

After exchanging the passwords, Feingold and Tarkington and the 15 other airmen took their places aboard the rowboats and then the rowers took them silently towards the gunboat anchored off shore.

Operation Bonaparte II on the night of the 26th to 27th February 1944 enabled the return to England of 16 airmen from the US Army Air Force and an airman of the Royal Air Force (the Belgian pilot Leon Harmel)

Edward J. Donaldson and Neelan B. Parker, escape buddies of Feingold and Tarkington from the departement of Oise as far as Paris, got away, like 22 other airmen, on Operation Bonaparte III on the night of 16th to 17th March 1944.

All of the airmen next reached London where they were interrogated by British and American officers of the Intelligence Services about the circumstances and the help which they received throughout their escape. After a few days or a few weeks they got back to the United States and again joyfully met their families who had stayed so long without any news.

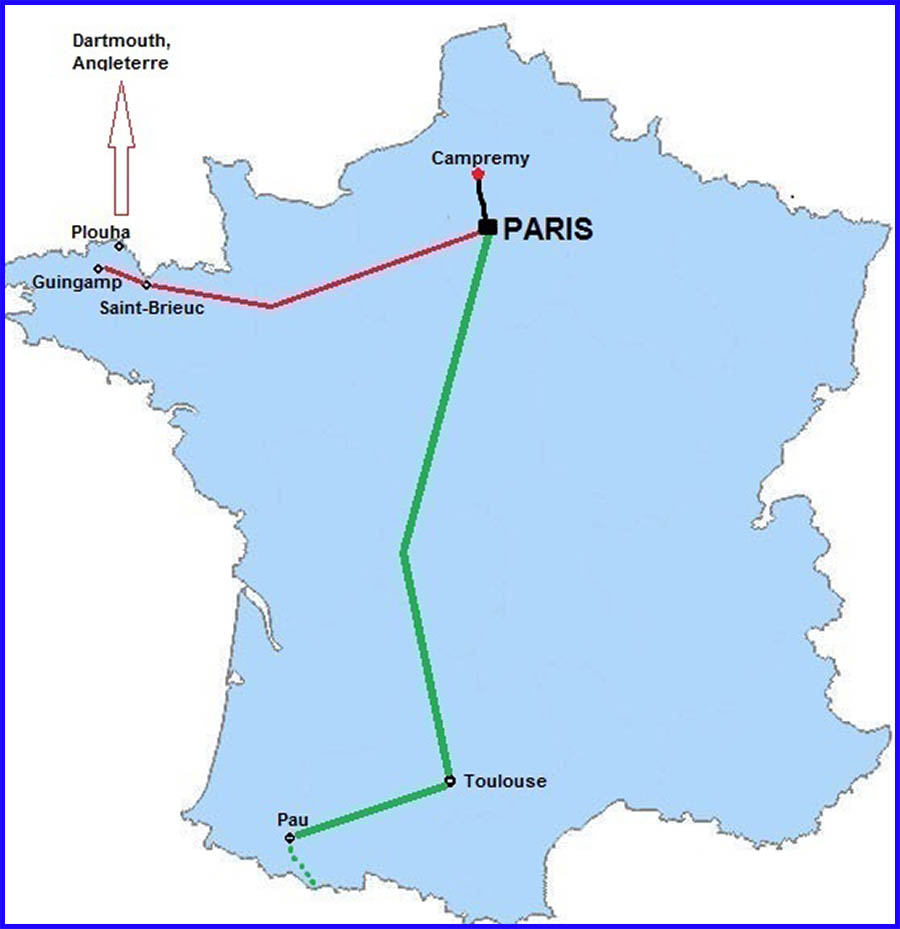

The different places of lodging of the airmen of “Destiny’s Tot”in the department of Oise

In red: the route followed by Smith, Booher, Mele, Eshuis, Feingold and Tarkington

In green: that followed by Morrison

After the war

The pilot Richard M. Smith was demobilised from the USAAF in June 1945. He followed his career for a time with Eastern Airlines before coming back to settle in Minnesota. He changed his job and worked in agriculture.

During several trips to France, he had the chance to meet his rescuers, both in Plouha and in the Oise, and was able to thank them personally.

Richard M Smith and the Begue family Richard M. Smith, William H. Booher, Louis Feingold and Anthony Onesi

during a meeting of the AFEES in 1997

In May 1996, he became President of the Air Force Escape and Evasion Society (AFEES) which right from the start allowed contacts to be renewed between airmen themselves and their helpers.

Richard M. Smith died on 29th March 2013.

The co-pilot William H. Booher found employment as a pilot with the Consolidated Can Corporation. There were several occasions on which he was able to see his crew members again.

He died on the 4th September 2007.

Louis Feingold worked with his father in the clothing business in New York City. During a trip to France he was able to meet again some of his rescuers on the occasion of a meeting organised by the AFEES at Chantilly in 1975.

Louis Feingold died on the 25th October 2008.

A moving reunion at Chantilly (Oise) in 1975

Robert Eckert, Louis Feingold and Gaston Legrand

Warren C. Tarkington continued his career in the Air Force where he retired as a Major. He never came back to France but was able to meet one of his rescuers, Jean Crouet, when this latter undertook a journey to Chicago in 1948.

Warren C. Tarkington died on the 17th December 1964.

Alphonse M. Mele went to Florida where he opened an Italian restaurant which he ran with this wife.

He died in May 1982.

On returning to the United States, Jerry Eshuis was transferred to a crew of a B-29 Superfortress. He undertook 21 other missions in the theatre of operations in the Pacific. After being demobilised he worked in agriculture.

Well after the war, following a commemorative ceremony at Plouha, Jerry Eshuis returned to the Oise to visit his rescuers. At the Chateau de la Borde, he was able to meet the family de Baynast again at the very spot where he was operated on, on the 1st January 1944.

The meeting at Catillon with Gervais Gorge who came to his aid a very short time after his landing, was equally a very special moment. Gervais Gorge had kept since the war several effects belonging to the airmen.

Jerry Eshuis died on the 17th October 1995

After 18 months of captivity spent in Stalag Luft VI and Stalag Luft IV Anthony Onesi was repatriated to the United States. He specialised in electronic equipment for landing systems for airports, working for the FAA (Federal Aviation Administration).

He died on 2nd April 2012.

24-25 September 2024 - Visit of Laurie and Richard Feingold